Neighborhood Change and Displacement: The Case for a Conversion Fee in St. Louis

By Cecilia Boyers

Email the author: cjboyers95@gmail.com

St. Louis has a displacement problem. We may not have the same unaffordability crisis, red hot markets, and population boom as cities like Portland or San Francisco, but housing in some neighborhoods is becoming unattainable to middle- and lower-income families. This trend has predictable consequences: when residents can no longer afford certain areas, their housing choices become limited, and poverty is further concentrated in the areas that remain affordable. The good news is that the situation is not yet out of our control: now is the time to implement a strategic, proactive anti-displacement plan before it is too late.

Neighborhoods in or just south of the Central Corridor are seeing improving market strength, increased property values, higher income levels, and greater investment overall. In many ways, development is a good thing: we all want our home values to rise, vacant buildings to be rehabilitated, our schools to be well-funded, and our historic buildings preserved. But problems emerge when growth occurs without mechanisms in place to ensure that existing residents can stay in their homes and enjoy the benefits. In burgeoning St. Louis neighborhoods, rent is going up, white families are replacing Black families, and median household incomes are rising (and, unfortunately, it’s not because wages have suddenly become more livable).

Multi-unit conversions are one of several indicators that a neighborhood is seeing investment. These conversions, usually from two- to single-family or from four- to two-family dwellings, technically require a permit through the Building Division. In practice, however, developers commonly do not state their intentions to do a conversion in the rehabilitation process, leaving the City with an inadequate and almost certainly undercounted paper trail. Conversions are both a cause and a result of investment-related displacement. When a building that previously offered several naturally affordable housing units is rehabbed into a large, expensive single-family home, the families that lived there before can no longer afford it. The number of available housing units overall is reduced, further limiting attainable housing options.

Before and after shots of a two-family building in Tower Grove South bought for $138k in 2012, converted for $100k, and sold this year (2021) as a single-family home for $550k (from NextSTL)

In an attempt to more comprehensively understand the state of conversions in St. Louis, Alderwoman Megan Green (15th Ward) requested conversion data from the Assessor’s Office. While technically public data, it is not published by the City.

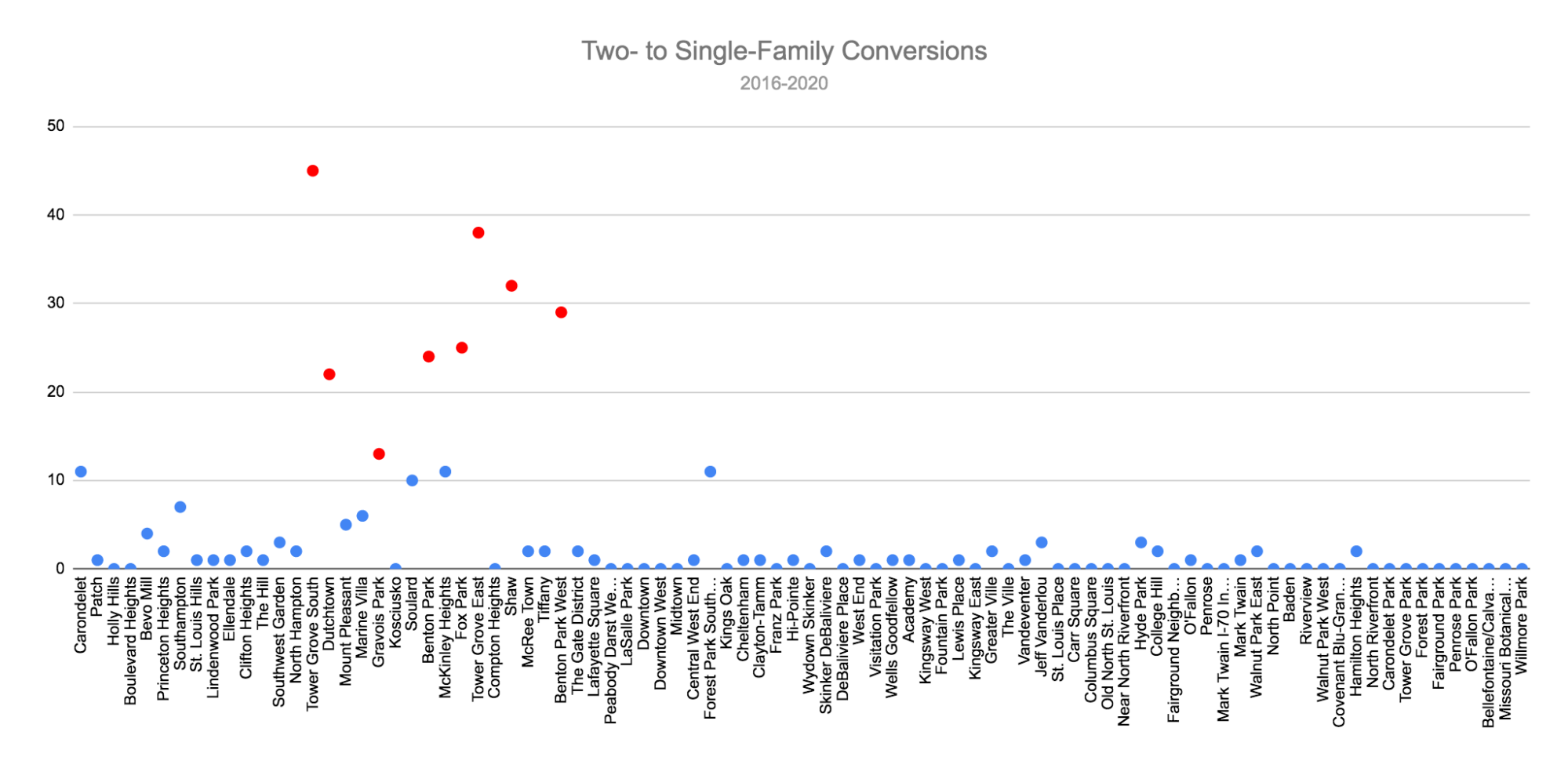

According to the Assessor’s Office, St. Louis City has lost at least 389 units to conversions since 2016. The vast majority of neighborhoods had no conversions at all, or perhaps one or two, but several had numbers of conversions in the double digits. I selected the 8 neighborhoods with the most conversions (Tower Grove South, Tower Grove East, Shaw, Benton Park West, Fox Park, Benton Park, Dutchtown, and Gravois Park) and compiled tract-level data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to consider correlations between conversions and other indicators of displacement in the past decade (table here).

Conversion data from Assessor’s Office (2016-2020)

For the most part, the neighborhoods with the highest rates of conversions did, in fact, meet criteria for other indicators of displacement of Black and low-income residents. For example, the number of conversions in Tower Grove South far surpassed other neighborhoods, with 45 conversions of two- to single-family homes since 2016, accounting for 13% of all conversions. Over the past decade, this area has become whiter and more expensive, with a significant increase in market strength and median household income (47% compared to 30% Citywide). In that time, Black residents have moved out (27% decline) as white residents have moved in (12% increase) at a rate significantly more acute than in St. Louis overall. Similarly, Tower Grove East, with the second highest number of conversions (38), saw median household income increase by 40% and a similar racial demographic change. There, housing is becoming not only less affordable, but also more scarce: TGE lost a total of 623 housing units since 2016, accounting for 30% of all units lost throughout the City. Perhaps the most conspicuous example of unattainability is Shaw, with the third highest number of conversions (32). Shaw has seen sharp increases in home values, rent, and overall cost of living that far surpass the City overall. Most notably, Shaw has seen a 53% increase in median household income since 2010, a striking white population increase of 40% and a Black population decrease of 27%. These trends, correlating conversions with other indicators of displacement, are similar for other high-conversion neighborhoods, such as Benton Park West, Benton Park, and Fox Park.

Four-family in Benton Park West converted to two separate townhomes (from @stlrainbow on Twitter).

Not all high-conversion neighborhoods are seeing displacement. Dutchtown and Gravois Park had relatively high numbers of conversions, but have not seen home values, rent, or market strength increase significantly. They have experienced neither a rise in incomes nor a notable displacement of Black residents replaced by white residents (although Gravois Park did see a greater decrease in the Black population than the City overall). The prevalence of conversions, high density, and proximity to growing areas, however, may be signs that investment-related displacement is on the horizon. Since 2016, Dutchtown lost 639 units and Gravois Park lost 510 units, representing 31% and 25% of total lost housing units in STL respectively. These will be neighborhoods to watch in the coming years, and preventative anti-displacement efforts should be considered here.

Alderwoman Megan Green (15th Ward), Alderwoman Annie Rice (8th Ward), Alderwoman Christine Ingrassia (6th Ward), and Alderman Dan Guenther (9th Ward) are developing new legislation imposing a fee on two- to single-family and four- to two-family conversions, similar to a bill recently passed in Chicago. In markets that are heating up, preventing conversions from happening entirely is like trying to put the toothpaste back into the tube: it would be unrealistic, and perhaps unwise, to impose a disincentive powerful enough to curb rehabs. But a fee could generate revenue to preserve, create, and fund affordable housing units to protect and diversify residents’ options and interrupt the cycle of concentrating poverty in still-affordable areas. The fee would only apply in neighborhoods that meet criteria demonstrating rapid growth so as not to hinder investment in areas that desperately need it.

An unchecked conversion process reduces the number of available affordable units in a given neighborhood, limiting housing options for low-income families. Areas benefiting from recent investment have a responsibility to promote affordability and therefore mitigate concentrated poverty elsewhere. Economic development at the expense of the choices and well-being of lower-income or Black St. Louisans is a strategy that is neither equitable nor sustainable. The City should consider a multi-unit conversion fee as part of an equitable economic development plan. It is impossible to entirely reverse the impacts of a long, sordid history of discriminatory housing policy in St. Louis, and often the pursuit of both growth and equity seems daunting. Nonetheless, we can and should begin confronting our troubled legacy by imposing and enforcing strategic interventions to harness the benefits generated by the private market and leverage them for the public good.

The views expressed in this blog post belong to the author and do not represent the views of the Affordable Housing Trust Fund Coalition, the Community Builders Network of Metro St. Louis, URBNRX, or Osiyo Design + Engagement. If you'd like to contribute to the St. Louis affordable housing conversation by submitting a piece for publication in this blog, please contact us.